It’s time to do away with work-life balance

The explosion of research on “work-life balance” is not new; if anything, it keeps accelerating, taking on new areas of focus, dimensions and associated analyses.

My goal in this piece is not to add to the explosion, but instead to question the concept of work-life balance itself.

What we mean when we say “work-life balance” is not well represented by the phrase or the associated research. Because of this, resources, benefits and the way we choose our priorities can be entirely misdirected.

“Work-life balance” deserves a reexamination, a new perspective, and new phrasing altogether.

Work-Life Balance in Organizational Psychology

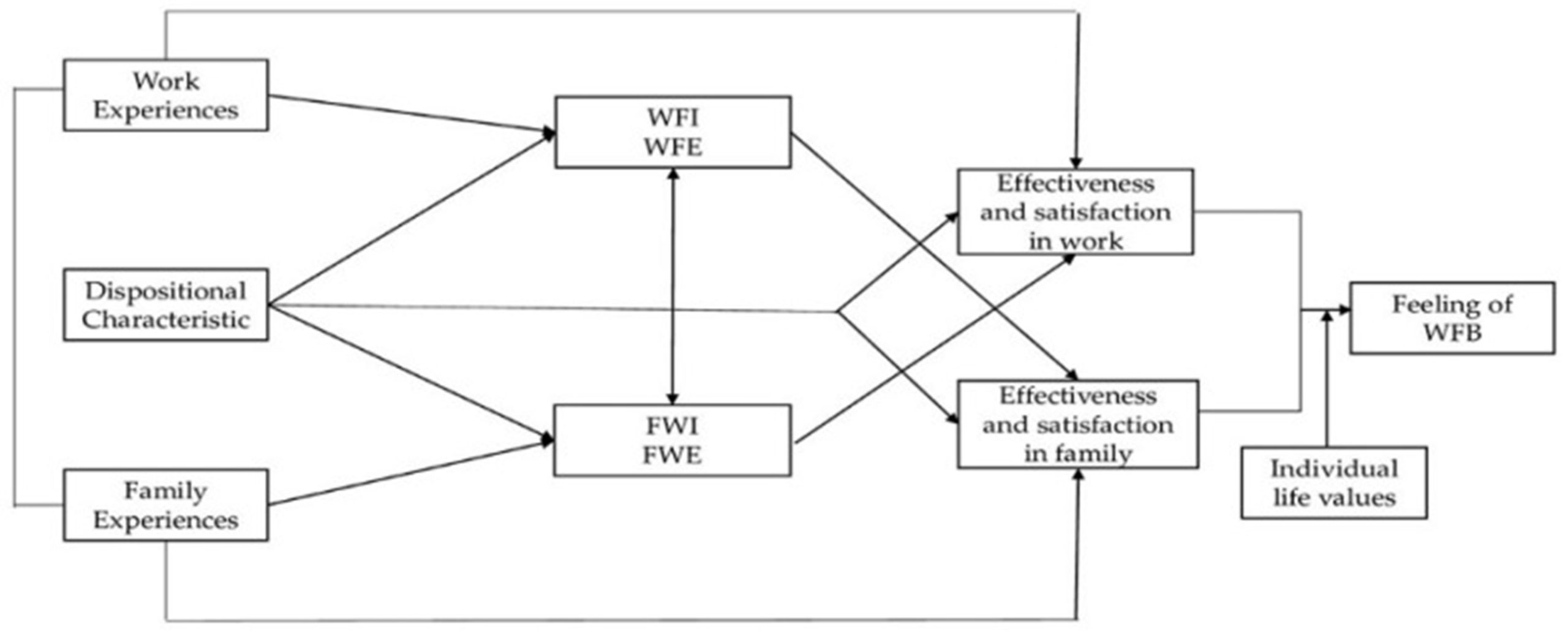

In their seminal study*, JH Greenhaus and TD Allen defined work-life balance as “an overall appraisal of the extent to which individuals’ effectiveness and satisfaction in work and family roles are consistent with their life values at a given point in time.”

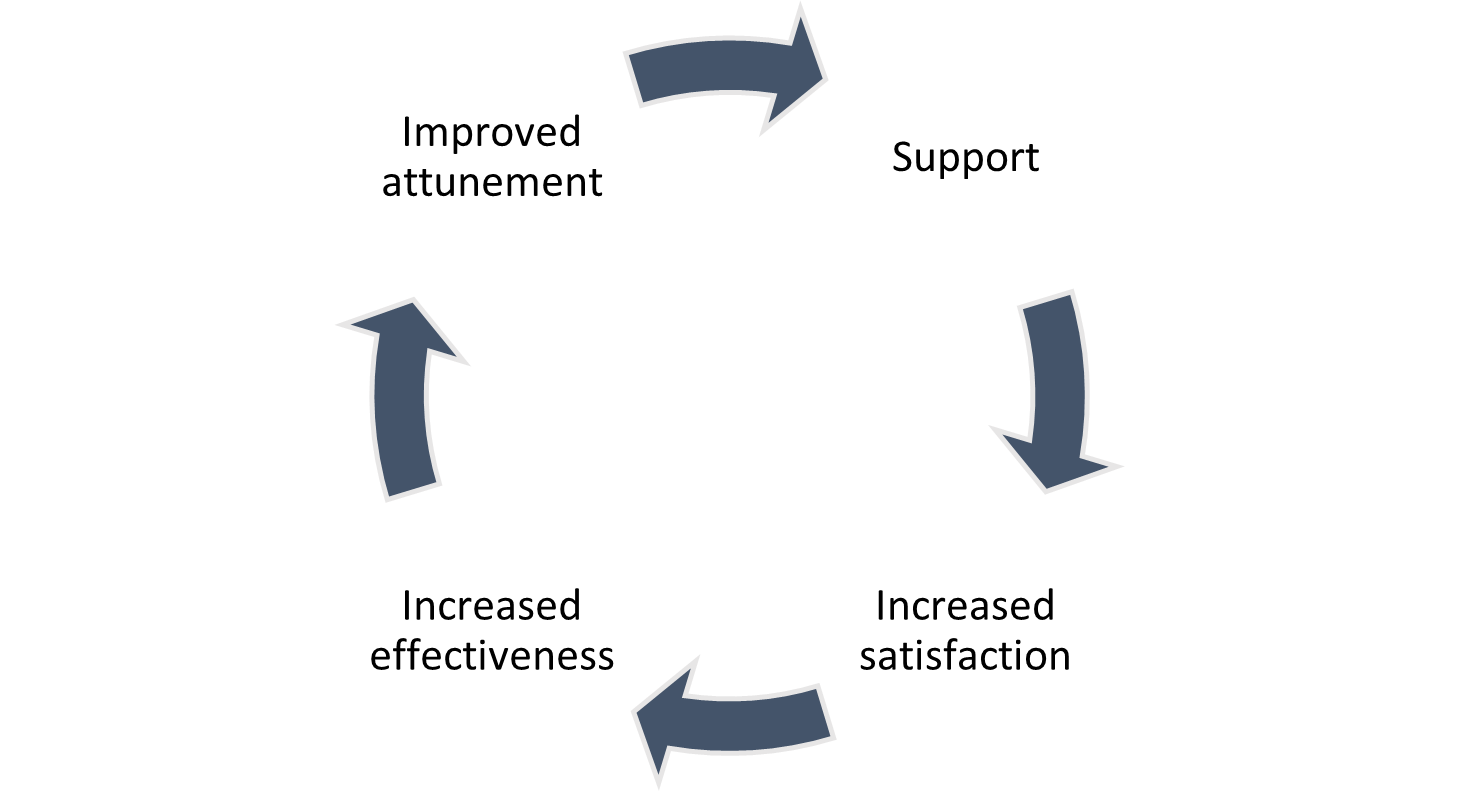

One of the outputs of their study was a conceptual “work-family balance model,” pictured below, which is a visual representation of this definition.

*Greenhaus J.H., Allen T.D. Work–family balance: A review and extension of the literature. In: Quick J.C., Tetrick L.E., editors. Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology. American Psychological Association; Worcester, MA, USA: 2011. pp. 165–183

The main inputs of their model — i.e. the elements that contribute to feeling more or less balanced — are these factors:

- Work-family conflict (WFI) and family-work conflict (FWI), defined as “a form of… conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect.”

- Work-family enrichment (WFE) and family-work enrichment (FWE), defined “as the extent to which experiences in one role improve the quality of life in the other”.

Both sets of factors (WFI/FWI and WFE/FWE) also impact effectiveness and satisfaction at work and within an individual’s family structure.

This model coheres with our common sense understanding of work-life balance, to some extent:

- When our work and our family lives are in conflict, we feel less satisfied and effective in both arenas, as well as less balanced on the whole.

- When our work and our family lives enrich one another, we feel more satisfied and effective in both arenas, as well as more balanced on the whole.

What’s Wrong with the Greenhaus/Allen Model – and “Work-Life Balance” Overall

Life vs. Family

One of the most striking things about the Greenhaus/Allen study, and subsequent work that builds off of it, is that the term “work-life balance” is almost immediately substituted with the term “work-family balance.” That substitution is far too simplistic for the many dimensions in our lives outside of work and family, including our friendships, spiritual lives, hobbies, self-care habits, physical and mental health, etc.

While the substitution of “life” with “family” in the Greenhaus/Allen study is glaringly obvious, this reductive thinking happens outside of scholarly papers, as well. Think about corporate policies aimed at “work-life balance.” The most basic of them only address family matters, like parental leave, family bereavement, childcare, and the like. But if we’re truly in touch with our core values in all aspects of our lives, we’re not solely focused on work and our families.

Work-life balance, then, should encompass far more than our family lives, and corporate policies aimed at supporting employees should treat it as such.

Work vs. Life

Another aspect of the Greenhaus/Allen model (and the phrase “work-life balance”) I take issue with is that both force differentiation between work and life. Work IS part of our lives, so how can we – and why should we – differentiate between them? For better or worse, work is woven into the very fabric of our daily lives. Even with strict boundaries preventing us from answering emails at night or logging on during the weekend, work has a profound impact on our identities, moods, friend groups, social and economic status, and more.

What’s worse, forcing a differentiation through the phrase “work-life balance” sets us up for failure. It makes an individual feel like a failure because he’s thinking about a work project during his toddler’s bath time, or because she has to make a doctor’s appointment during working hours. Since when were human beings made to be so compartmentalized?

The differentiation itself is a misleading notion, and should be eliminated.

Demanding vs. Providing

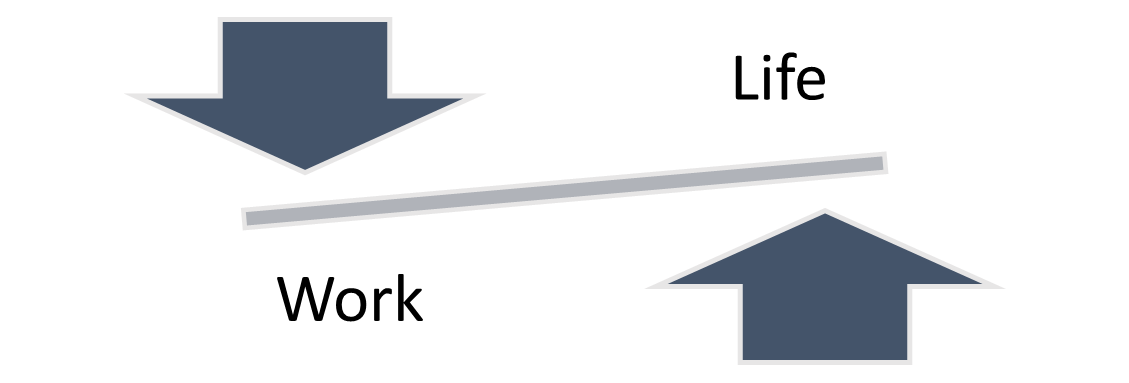

Finally, the word “balance” suggests something different than we mean it to. It implies that work and life are just DEMANDING things of you, pulling you in all different directions, rather than PROVIDING you with purpose, fulfillment, and opportunities for growth.

If we have to balance DEMANDS between work and life, it conjures up the image of a see-saw, with work and life on opposite ends, always pulling against one another. In this analogy, an individual can only feel balanced when he or she finds the perfect Goldilocks-type sweet spot between the two. It wouldn’t be a sustainable sweet spot at all. It’d be momentary, fleeting, and possibly not even attainable.

A New Perspective

While I disagree with the Greenhaus/Allen model – and the way we use the term “work-life balance” colloquially today – Greenhaus and Allen did refer to the pieces of what I think most people mean when they use the term.

Here’s what I think most people mean when they say they want “work-life balance”:

- To feel satisfied with the important aspects of their lives

- To feel effective in the important aspects of their lives

- To be aligned with their core values in the important aspects of their lives

Given the issues I take with the term “work-life balance,” and these three components of my definition, I’ve called this feeling “attunement.”

Dictionary.com defines attune as “aware of and in harmony with some principle, ideal, or state of affairs.”

This model is much more stable than the see-saw analogy discussed earlier. Instead of the constant push and pull between work and “life,” e.g. family or some other counterbalancing force,

The model is actually cyclical and self-perpetuating.

It all starts with support – support that ensures you’re aligned with your core values. The more support an individual receives, the more satisfied he or she feels, which leads to increased effectiveness in that area of life. That, then, leads to greater attunement, which comes back around to getting (and giving) even more support, and so on.

Lacking Attunement

One of the easiest ways to figure out whether a person is attuned is to look for signs that they’re lacking it. Here are some of the most obvious ones:

- They’re at some stage of burnout. This is typically, but not always, driven by not being aligned with core values in an important area of life.

- They’re dissatisfied with something: how they’re spending their time, some aspect of their lives, the quality of their relationships.

- Their focus is on others, not at all on self. This can happen in any arena, including at work (e.g. not doing any personal development, learning, etc.) This can lead to decreased effectiveness.

This is where support matters. Support drives that self-perpetuating attunement cycle, so it’s critical for others to step in and help. However the quality of the support matters. As discussed earlier, it’s not enough to focus solely on, for example, parental leave or childcare or any other singularly-focused aspect of employees’ lives. Instead, be holistic with support. Seek to understand what drives employees’ satisfaction and effectiveness. Ask about their core values and discover where any gaps may lie. That’s where the support must start.